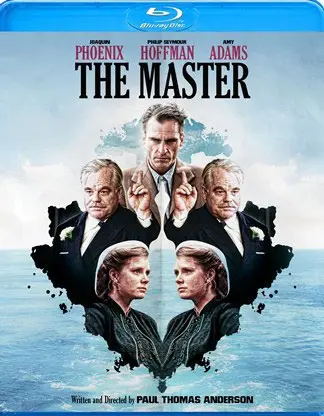

Paul Thomas Anderson may have a better grasp of characterization than any filmmaker working today. For proof, look no further than The Master.

Paul Thomas Anderson may have a better grasp of characterization than any filmmaker working today. For proof, look no further than The Master.

Often when thinking about Anderson’s career, the films most pointed to are Boogie Nights, Magnolia, and There Will Be Blood, all of which deal with big themes and broad emotions on a large scale. Forgotten are the smaller, more intimate films like the eternally-overlooked Punch-Drunk Love and the all-but-forgotten Sidney (or Hard Eight; depends on who you talk to).

But with all the attention The Master has received this past year (including its three Oscar nominations), it seems like Anderson’s latest offering may stick around in the collective cinematic consciousness.

The movie follows Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), a naval veteran who’s just returned from his tour in World War II. Our first impressions suggest that his experiences in the war may have driven him into a shell-shocked state, but as we learn more about Freddie in the course of the movie it becomes obvious that his service only exacerbated an already-unstable mind.

He’s an alcoholic who makes his own special brew using, among other things, paint thinner, he seems to delight in picking fights with strangers, and is more than a little obsessed with sex.

While on the run from some co-workers he’s rubbed the wrong way, Freddie stows away on a yacht departing San Francisco and bound for New York. Here, Freddie meets Lancaster Dodd (Phillip Seymour Hoffman), the founder of a spiritual movement called ‘The Cause’ (loosely based on L. Ron Hubbard and the Church of Scientology, respectively).

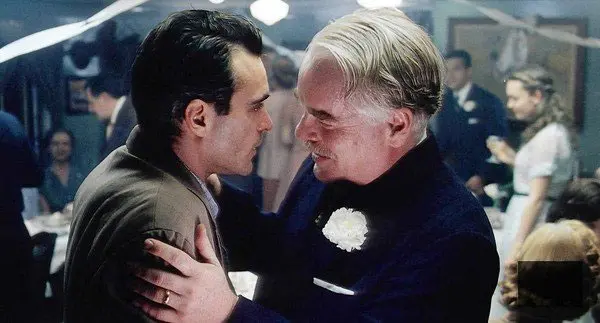

Rather than alert any authorities or throwing him overboard, Dodd seems instantly intrigued by Freddie and becomes especially fond of one of the latter’s home-grown alcoholic concoctions.

It’s this meeting and the dynamic that develops as a result that becomes the fulcrum of the movie and the heart of all the events that follow – these are two men seeking answers to a mystery. On one hand there is Dodd, driven by his own curiosity and bent on solving some unseen mystery to Freddie; he wants to understand what makes this strange, broken man tick.

Then there’s Freddie. Phoenix seems to play Freddie as a man who knows he’s a broken soul – he doesn’t know why he’s broken, and he doesn’t much care. His mystery is two-fold: He doesn’t understand why he can’t apply himself to seeking out the things he wants out of life, and he doesn’t understand Dodd’s need to answer the same question.

There’s a deep and genuine love that Dodd holds for Freddie, masked with his own pseudo-scientific curiosity. At their first meeting, it seems as though Dodd only plans to use Freddie as a guinea pig to demonstrate the positive effects of following The Cause. As the relationship develops, though, Dodd seems to take Freddie in as something of a surrogate son.

Amy Adams also stars in the film as Dodd’s wife, Peggy. In a lesser movie, both Adams and Anderson might wind up collaborating to make Peggy nothing more than a jealous wife – a character with shallow motivations no more complex than wondering, “What’s so special about Freddie?”

And while this aspect of Peggy’s character is present, that’s not the full extent of it. We learn not long after Peggy’s introduction that she is as much an architect of The Cause as her husband. So rather than focusing solely on how this strange new man impacts her life, she also has her concerns about how it will affect the movement.

I’m a big fan of Anderson’s and have been for some time, and the reason for that is that his movies are almost entirely character-driven, and The Master is no exception. If you were to present this movie to a film school class and ask them to break it down into a three-act structure, I imagine most would have a difficult time with it. The story doesn’t conform to any kind of rigid, industry-tested and studio-approved method. It tackles its questions in its own time – the audience can either keep up with it or they can’t.

There’s a moment when Dodd first interviews Freddie in which Freddie flashes back to a memory of the proverbial girl who got away. That’s as traditional as this movie gets.

And the cast is as up to the challenge as its writer/director, particularly Hoffman and Adams.

Hoffman’s take on Dodd is a fascinating one and one that’s difficult to describe – which, considering the character, is fitting and a testament to Hoffman’s ability. Dodd is a man who seems to be made of mysteries. He’s committed to his made-up philosophy, but we’re left in the dark as to what spawned it. Hoffman plays Dodd as a man who’s already answered all of his questions, aside from the ones we’re privy to.

If we want to understand Dodd, we have to work backwards based on what Anderson and Hoffman tell us. It’s refreshing to see a director and an actor collaborate in such a way as to almost force the audience to ask questions and become engaged.

Adams is likewise brilliant, using her trademark “girl next door” charm to endear us to her upon first meeting her – we think we know what we’re in for. Then there’s a scene with Dodd and Peggy in their bathroom that’s sure to raise an eyebrow if you haven’t seen the film, and we abruptly realize that there’s more to this woman.

And, gloriously, we never do manage to learn it all.

Then there’s Joaquin Phoenix. His performance as Freddie Quell is well-crafted, and his interpretation of Freddie’s idiosyncrasies feels natural for the most part, particularly in terms of facial gestures and his vocal performance. It’s a very good performance, but it toes the line very delicately between well-crafted and manufactured.

There are elements to his posture and the delivery of certain lines that suggest Phoenix is trying too hard to make a character rather than become the character.

Having said that, the final scene in the movie makes a departure from the rest of the film’s seeming lack of structure to bring the story full circle, and in this one four-minute scene, any issues I might have had with the performance prior simply fall away. It’s one of the best endings to a movie I’ve seen in quite some time.

As great as this movie is, though, it isn’t without some flaws. Anderson unquestionably has strength both as a visual stylist, and he’s a superb writer of dialogue, but pacing has always been an issue for him, and this movie is no exception.

The story is constantly engaging, but there are long lulls, sometimes in the middle of a scene where the movie seems to grind to a screeching halt.

Also, there’s a small role in the film played by Laura Dern that seems out of place with the rest of the movie. Dern plays the part fine, but the role itself seems extraneous and contrary to the “let the audience answer their own questions” attitude of the rest of the film.

But these complaints are mere drops in the bucket.

The Master stands as another great achievement by a great filmmaker – one that I imagine will likely stand the test of time.

High-Def Presentation

Anchor Bay has brought The Weinstein Company’s production of The Master with an absolutely perfect visual transfer.

Much of the hype behind The Master, at least in terms of the technical side of filmmaking, revolved around Anderson’s choice to shoot the vast majority of the film in 65 mm film, and the 1080p AVC/MPEG4-encode presented here captures the movie in absolutely glorious detail. Colors are vibrant and lifelike, and every detail is nothing short of pristine.

There’s noticeable grain, but that has more to do with the lack of a digital intermediate than anything else. This transfer captures the vision captured by Anderson and director of photography Mihai Malaimare, Jr. perfectly.

Not to be outdone, the audio track, a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix, also shines. It’s a dialogue-heavy film and the mix ensures that not a single line is either inaudible or difficult to understand. The score by Johnny Greenwood gets appropriate attention. There were times when Phoenix’s choice of a voice for Freddie is hard to discern, and although that seems to be more the fault of the actor’s choice than anything else, there seems to be extra muffling whenever he speaks.

It’s a mild complaint, but it is a (very) occasional distraction.

Beyond the Feature

And we’re back to lacking bonus features for movies that are anything but lacking.

The highlight of the bonus features is the experimental manner in which the deleted scenes are presented. Rather than a one-by-one presentation, the deleted scenes are presented essentially as a short film, entitled Back Beyond (20 min), complete with an original score by Greenwood. It’s a neat experiment but comes across as disjointed.

Speaking of disjointed, the 8-minute feature Unguided Message is a unique behind-the-scenes doc that cobbles together alternately hectic and boring moments of the making of a film. There’s no focus on any given department or aspect of filmmaking (good), but there’s no focus on anything at all (bad). It’s a weird mishmash that just never seems to come together.

The only real insight into the movie’s conception comes from the inclusion of the 1946 short film from John Huston, Let There Be Light, a 58-minute feature about the effects of long-term military service on WWII vets. The short focuses extensively on hypno-therapy, which is the basis of Dodd’s primary treatment methods in the primary film. It’s an interesting film and lends an understanding of the birth of the film in Anderson’s head. Having said that, the transfer is a little worse-for-wear and is pretty hard on the eyes at certain points.

Rounding out the bonus features is a collection of nine Trailers and Promotional Spots that totals about 17 minutes.

Despite the hit-and-miss bonus features, The Master is a fantastic film. There’s no guarantee that you’ll understand it or that you’ll be able to follow the story – but I can guarantee that the characters and the actors who bring them to life as well as the visual mastery of Paul Thomas Anderson will keep you engaged for two-and-a-half hours.

Shop for The Master on Blu-ray for a discounted price at Amazon.com (February 26, 2013 release date)